The Four Fundamental Subspaces

- The Central Question: What Structure Does the Solution Set of Ax = b Have?

- Basis, Dimension, and Rank

- Defining the Four Subspaces

- Matrix Shapes and Geometry

- Integrating Concepts: The Complete Solution

- Summary: The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra

- Fundamental Theorems

- Applications in Data Science and Machine Learning

- Guided Problems

- References

The Central Question: What Structure Does the Solution Set of Have?

We want to solve a system of linear equations in unknowns, written as . In the "row picture," each of these equations defines a hyperplane in -dimensional space. The goal is to find a solution , which is a single point of intersection that lies on all of these hyperplanes.

This geometric view presents three possibilities:

- One Solution: The hyperplanes intersect at a single point.

- No Solution: The hyperplanes have no common intersection point (e.g., two planes are parallel).

- Infinite Solutions: The hyperplanes intersect on a larger set, such as a line or a plane (e.g., three planes intersect on a common line).

The homogeneous case is a related problem where . Since all hyperplanes must pass through the origin, (the "trivial solution") is always one answer. The fundamental question becomes: Do the hyperplanes intersect only at the origin, or do they also intersect along a larger set (like a line or plane) that passes through the origin?

Basis, Dimension, and Rank

Basis

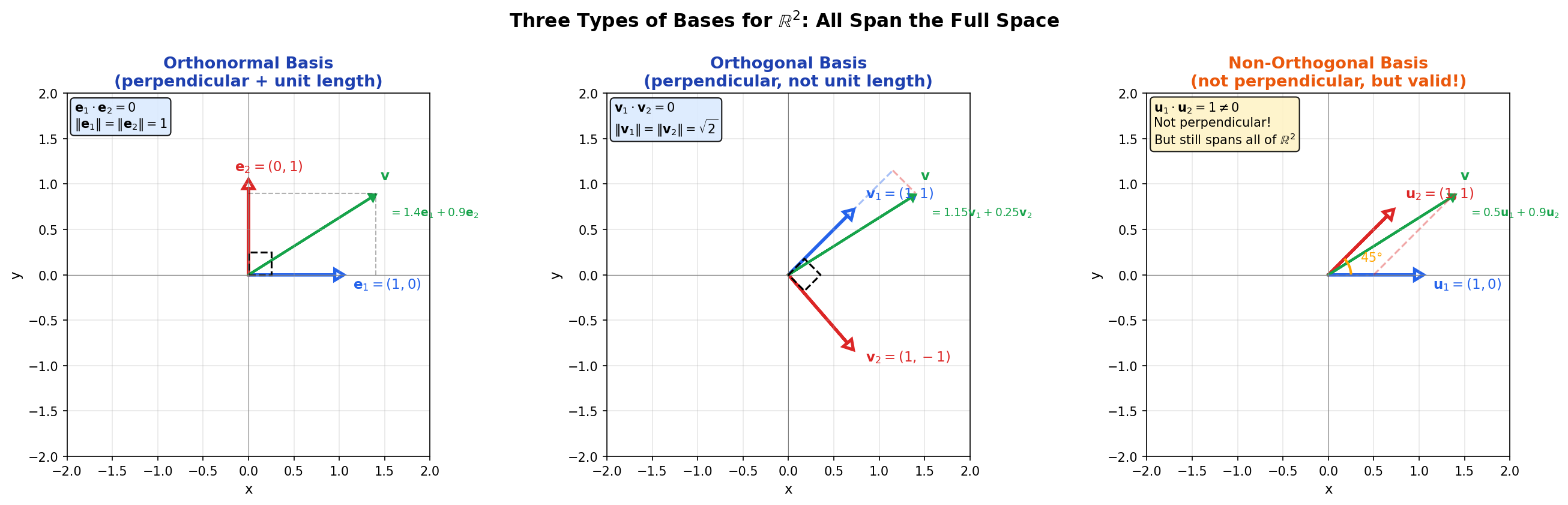

You can represent every vector in with combinations of the two vectors (orthonormal basis). It's also possible with (orthogonal basis) or even (non-orthogonal basis).

Figure: Three types of bases for . Left: Orthonormal basis. Middle: Orthogonal basis. Right: Non-orthogonal basis (not perpendicular, but still linearly independent and spans all of ).

The same vector (shown in green) has different coordinate representations in each basis.

- In the orthonormal basis (perpendicular and unit length), .

- In the orthogonal basis (perpendicular but not unit length), .

- In the non-orthogonal basis, .

The dashed lines show how is decomposed along each basis. Despite the different coefficients, all three representations describe the exact same point in .

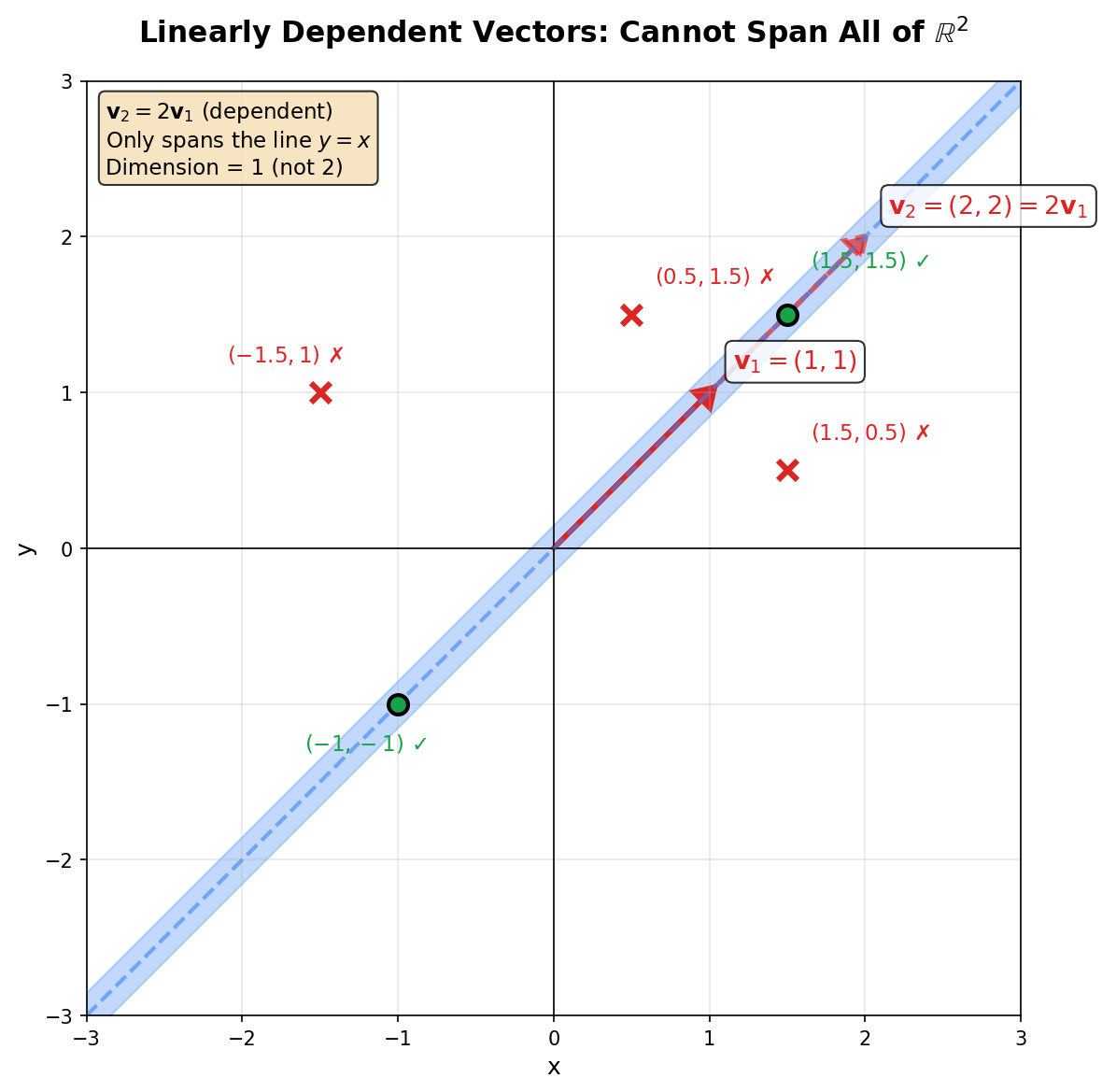

However, you cannot represent every vector in with combinations of two linearly dependent vectors like . Since the second vector is just times the first, they point in the same direction and only span a one-dimensional line (the blue shaded region in the diagram below), not the entire two-dimensional plane.

Figure: Linearly dependent vectors cannot span all of . Vectors on the line (green ✓) can be represented, but vectors off the line (red ✗) cannot.

From these examples, we observe a fundamental pattern: any set of linearly independent vectors can span a vector space and serve as a coordinate system to represent every vector in that space. In contrast, linearly dependent vectors (or a single vector alone) cannot span the entire space. This observation leads us to the formal definition of a basis—the minimal set of "building blocks" or "coordinate axes" for a vector space. A basis has just enough vectors: not too few (or it couldn't span the whole space) and not too many (or the vectors would be dependent, making some redundant).

A basis for a vector space is a set of vectors that satisfies both of the following properties:

-

Linearly Independent: The only solution to is when all coefficients . This means there is no redundancy—no vector in the set can be written as a combination of the others.

-

Spans the Space: Every vector can be expressed as a linear combination for some scalars .

Dimension

From the examples above, we see that any vector in can be represented by a linear combination of exactly two basis vectors, while any vector in requires exactly three basis vectors. This number of vectors in a basis is the dimension of the space—it measures the "degrees of freedom" or the number of independent directions in that space. All bases for the same vector space contain the same number of vectors.

Let be a vector space with a finite basis. Then every basis for contains exactly the same number of vectors.

The dimension of a vector space , denoted , is the number of vectors in any basis for .

Examples:

- A line has dimension 1.

- A plane has dimension 2.

- has dimension .

- If the nullspace of is the line spanned by , then .

Rank

Consider the matrix . The second column is twice the first column, making them linearly dependent. Both columns lie on the same line in . All vectors that can be created by combining these columns span only a one-dimensional line, not the full two-dimensional plane. The number of linearly independent columns (or equivalently, the dimension of the space they span) is 1. This number is called the rank of the matrix.

The rank measures how many independent columns a matrix has. This always equals the number of independent rows.

The rank of a matrix , denoted or , is the dimension of its column space: .

The dimension of the column space equals the dimension of the row space. Consequently, the number of pivot positions in is equal to the rank of .

📌 Proof via RREF

-

Row operations preserve row space: Elementary row operations (scaling, adding, swapping) create linear combinations of existing rows. The span of the rows remains unchanged.

-

Column dependencies are preserved: While column vectors themselves change, the linear relationships between them are invariant. If initially, this holds in the RREF.

-

Pivot count links both: In the final RREF "staircase" shape:

- Every pivot (leading 1) corresponds to a non-zero row

- Every pivot defines a linearly independent column

- Therefore: Number of Non-Zero Rows = Number of Pivot Columns

Conclusion: Row Rank = Column Rank = Number of Pivots.

How to Find Rank: The rank equals the number of pivots found by Gaussian elimination in the echelon form or reduced row echelon form .

Example:

This matrix has only one pivot (the 1 in position (1,1)), so .

Rank as Information Count

In a data matrix where rows are samples and columns are features:

- Redundancy: If a feature is a linear combination of others (e.g., "Price in Euros" vs. "Price in USD"), it adds no new dimension

- Rank: Measures the number of independent directions in the data—the true dimensionality of the "information manifold" the data lives on, ignoring redundant axes

- Deficient rank: Signals multicollinearity, causing instability in regression and non-unique solutions

Dimension vs Rank

Dimension and rank are related but describe different objects:

| Feature | Dimension | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| What it describes | A vector space or subspace | A matrix |

| What it measures | The number of vectors in any basis for the space | The number of independent columns (or rows) in the matrix |

| How to find it | Find a basis for the space and count the vectors | Count the pivots in the echelon form |

| Example | has dimension 3 A plane in has dimension 2 A line has dimension 1 | A matrix with 2 pivots has rank 2 A matrix where all columns are multiples of one vector has rank 1 |

Defining the Four Subspaces

To answer the questions we stated at first, let's consider the matrix below. For our examples, we will use this matrix with rank :

The Column Space

Consider the columns of our matrix : , , and . Notice that , so the third column is linearly dependent on the first two. All linear combinations of these three columns produce the same set of vectors as combinations of just and . This set forms a 2-dimensional plane in , not the full 3-dimensional space.

This set of all linear combinations of the columns is called the column space . It answers a fundamental question: which vectors can we reach by solving ? When we write with , we are asking whether we can find coefficients such that . This is precisely asking whether can be written as a linear combination of the columns. Therefore, has a solution if and only if .

The column space of an matrix is the set of all linear combinations of the columns of . Equivalently, .

It is a subspace of .

Key Properties:

| Property | Description | Our Example |

|---|---|---|

| Solvability | has a solution | must be in the plane spanned by columns 1 and 2 |

| Dimension | ||

| Basis | The pivot columns from |

Finding the Basis: Identifying Pivot Columns

To find a basis for , perform Gaussian elimination to identify the pivot columns:

The pivots (boxed) are in columns 1 and 2. The basis for consists of the corresponding columns from the original matrix (not from ):

Important: Always use the original columns, not the columns from the echelon form. Elimination changes the column space but preserves which columns are independent.

The Nullspace

Recall that our matrix has the dependency . We can rewrite this as , or equivalently:

The vector is a "recipe" that combines the columns to produce zero. This recipe encodes the dependency relationship among the columns. The set of all such recipes is called the nullspace .

In contrast, consider the identity matrix with linearly independent columns. To find vectors such that : The only solution is and , giving . The nullspace contains only the zero vector, , confirming the columns are independent.

The nullspace reveals the redundancy in a matrix. If (only the zero vector), the columns are independent. If contains non-zero vectors, the columns are dependent. The nullspace also determines solution uniqueness: if solves , then the complete solution set is for all .

The nullspace of an matrix is the set of all solutions to the homogeneous equation . That is, .

It is a subspace of .

The rank of a matrix plus the dimension of its nullspace equals the number of columns of :

Proof via Counting: In RREF, every column falls into one of two categories:

- Pivot Columns: Correspond to the Rank ()

- Free Columns: Correspond to free variables in . Each free variable generates one independent basis vector for the Nullspace.

Therefore: Total Columns () = Pivot Cols () + Free Cols (Nullity).

Conservation of Information: This theorem acts as a conservation law for linear transformations :

- Input (): Total dimensions of information entering the system

- Rank (): Information that survives the transformation (mapped to the output space)

- Nullity (): Information that is destroyed (mapped to zero)

Key Properties:

| Property | Description | Our Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | (number of free variables) | |

| Basis | Special solutions (set each free variable to 1) | (a line in ) |

| How to find | From : set | and |

Finding the Basis: Solving from Reduced Form

To find a basis for , reduce the matrix to reduced row echelon form (RREF) and solve :

Identify pivot and free variables:

- Pivot columns: 1, 2 (containing pivots)

- Free column: 3 (no pivot)

- Therefore: are pivot variables, is a free variable

From the RREF, read off the system:

Find special solutions: Set each free variable to 1 (one at a time if there are multiple):

For : we get

Therefore:

Additional Examples:

For the identity matrix , the only solution to is . Therefore and the columns are independent.

For , the second column is twice the first. The vector satisfies because . This recipe explicitly shows the dependency: Column 2 = 2 × Column 1.

The Row Space

The rows of our matrix are , , and . Notice that , making the third row dependent. All linear combinations of these three rows form the same set as combinations of just the first two. After Gaussian elimination, has two non-zero rows that span this same space. The row space is a 2-dimensional plane in .

The set of all linear combinations of the rows is called the row space, denoted (since rows of are columns of ).

The row space of an matrix is the set of all linear combinations of the rows of . Equivalently, it is the column space of .

It is a subspace of .

Key Properties:

| Property | Description | Our Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | (row rank = column rank) | |

| Basis | The non-zero rows from echelon form (or ) | |

| Important | Gaussian elimination preserves the row space |

Finding the Basis: Non-zero Rows from Echelon Form

To find a basis for , perform Gaussian elimination and take the non-zero rows from the echelon form:

The non-zero rows of form a basis for :

Why this works: Row operations create linear combinations of the original rows. The non-zero rows of are still combinations of the original rows, and they span the same space as the original rows. Moreover, they're linearly independent (by construction of RREF), giving us a basis.

Key difference from column space: For row space, we use rows from the echelon form. For column space, we use columns from the original matrix. This is because elimination preserves row space but changes column space.

Orthogonal Complement with Nullspace:

The row space and the nullspace are orthogonal complements in . Consider any row of and any nullspace vector . Since , each row dotted with gives zero: . Since row space vectors are linear combinations of rows, every vector in is perpendicular to every vector in .

This means:

- Together they span all of : any uniquely decomposes as where and

- Their dimensions add up to :

For our matrix:

- Row space basis:

- Nullspace basis:

Verification:

Application: Row Space Component of Solutions

When solving , the complete solution is where is a particular solution and .

Among all particular solutions, there is a unique one lying in the row space , perpendicular to . The matrix only "sees" this row space part: .

Example: For , one particular solution is . To find the row space component, solve:

Therefore: is the unique row space solution.

💡 Question: Among infinitely many particular solutions to , why is there exactly one in the row space?

Answer: This follows from the orthogonal complement structure. Since and are orthogonal complements in , any vector has a unique decomposition as where and .

For any particular solution , we can write it as . The row space component is the same for all particular solutions (since they differ only by nullspace vectors). Therefore, there is exactly one particular solution that lies entirely in the row space: the one with zero nullspace component.

The solution set forms a line (or higher-dimensional affine space) parallel to . This line intersects the row space at exactly one point, since .

The Left Nullspace

During Gaussian elimination on our matrix , we discovered that row 3 equals row 1 plus row 2. This means:

The coefficient vector gives a combination of rows that produces the zero row. We can write this as , or equivalently . The set of all such vectors is called the left nullspace, denoted . It is called "left" because multiplies from the left: .

The left nullspace of an matrix is the set of all solutions to the equation . Equivalently, it is the set of all vectors such that . It is a subspace of .

Key Properties:

| Property | Description | Our Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | (number of zero rows in echelon form) | |

| Basis | Found from row dependencies during elimination | (a line in ) |

| Interpretation | Coefficients that make rows combine to zero |

Finding the Basis: Backtracking Through Elimination

For our matrix, the elimination process is:

The final zero row tells us that row 3 of equals zero. But how does this give us the left nullspace? We need to trace back through the elimination operations to express this in terms of the original rows of .

Step-by-step backtracking:

Starting from the final form: Row 3 of =

Working backwards:

-

Last operation ():

- Before this step, row 3 was (same as row 2)

- So:

- This means: Row 3 (final) = Row 3 (after step 2) - Row 2 (after step 1)

-

Second operation ():

- Row 3 after this step was

- Row 3 before was (original row 3)

- Row 1 after first step was (original row 1, unchanged)

- So: Row 3 (after step 2) = Original Original

-

First operation ():

- Row 2 after this step was

- So: Row 2 (after step 1) = Original Original

Combining everything:

Row 3 (final) = Row 3 (after step 2) - Row 2 (after step 1)

Substituting:

This gives us the coefficients that make the original rows combine to zero. Therefore is a basis for , making it a line in .

📌 Example: Matrix with multiple left nullspace basis vectors

Consider a matrix with rank 2:

Since , the left nullspace has dimension 2. Elimination gives:

We have two zero rows, so we need to find two dependency relationships.

For the 3rd zero row:

- Final: Row 3 = 0

- Operations:

- Therefore:

- First basis vector:

For the 4th zero row:

- Final: Row 4 = 0

- Operations:

- Therefore:

- Second basis vector:

The left nullspace is , a 2-dimensional plane in .

Orthogonal Complement with Column Space:

The left nullspace and the column space are orthogonal complements in . If , then , which means is perpendicular to every column of . Since column space vectors are linear combinations of columns, every vector in is perpendicular to every vector in .

For our matrix:

- Column space basis:

- Left nullspace basis:

Verification:

Their dimensions add up to : .

Matrix Shapes and Geometry

The shape of a matrix () fundamentally determines what kinds of solutions are possible.

Fat Matrices (m < n): More Features Than Samples

- Shape: Wide and short (more columns than rows)

- Constraint: Max rank is , so

- Nullspace: Since , the nullspace is always non-trivial

- Implication: Some information is guaranteed to be destroyed; the transformation cannot be injective

Example: A matrix (10 samples, 1000 features) must have nullspace dimension .

Skinny Matrices (m > n): More Samples Than Features

- Shape: Tall and narrow (more rows than columns)

- Constraint: Max rank is , so

- Left Nullspace: Applying Rank-Nullity to :

- Implication: The column space cannot fill the output space ; the transformation cannot be surjective

Unreachable Space: The column space is a lower-dimensional subspace (e.g., a 2D plane) inside the larger output space (e.g., a 3D room). The left nullspace represents directions orthogonal to the data—outputs the model cannot reach.

Trivial vs. Nontrivial Nullspace

| Nullspace Type | Condition | Columns | Geometry | Solutions to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trivial | Linearly independent | Injective (one-to-one) | At most one solution | |

| Nontrivial | Linearly dependent | Non-injective (many-to-one) | If solvable, infinitely many |

When the nullspace is nontrivial, a line (or plane) of inputs collapses to a single output point.

Integrating Concepts: The Complete Solution

The four subspaces provide a complete answer to the two fundamental questions about .

The system of linear equations has a solution if and only if is orthogonal to the left nullspace .

Consider our matrix with left nullspace basis .

Example 1: Does have a solution?

Check: ✓

Yes, it has a solution.

Example 2: Does have a solution?

Check: ✗

No, it has no solution.

Why this works: The left nullspace basis encodes the row dependency: , meaning . If has a solution, this same dependency must hold for : we need .

Let be an matrix. The following are equivalent:

- (full row rank)

- has a solution for every

Example: has full row rank. For any , the system always has a solution.

When , the solvability condition is vacuously satisfied for all .

💡 Question: Why are these four conditions equivalent?

Why does imply full row rank, full column space, and universal solvability?

Brief Proof Sketch:

(1) ⟺ (2): From the Fundamental Theorem, . Therefore:

(2) ⟺ (3): Since , we have: (A subspace of with dimension must be the whole space.)

(3) ⟺ (4): By definition: Therefore, means every can be written as for some .

Key Insight: When there are no row dependencies (), all rows are independent, giving full row rank. This means the rows span all of , so the columns can reach any .

How many solutions are there?

If is a particular solution to the non-homogeneous equation , then the general solution is given by: where represents an arbitrary vector in the nullspace .

For our matrix (with ) and , one particular solution is . The complete solution is:

This is a line parallel to the nullspace, shifted from the origin by .

The full solution set is .

Cases:

| Condition | Solution Structure | Geometric Picture |

|---|---|---|

| (unique) | Single point | |

| Line through | ||

| Plane through |

Summary: The Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra

The four fundamental subspaces capture different aspects of a matrix :

| Subspace | Lives in | Dimension | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Column Space | Where must be for solvability | ||

| Nullspace | Coefficients that make columns vanish | ||

| Row Space | Where actually contributes | ||

| Left Nullspace | Coefficients that make rows vanish |

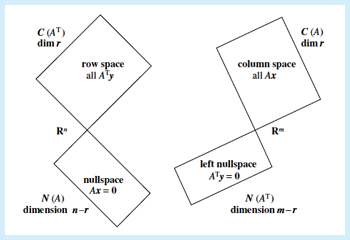

The Fundamental Theorem

For an matrix with rank :

Part 1: Dimensions

Part 2: Orthogonality

These orthogonal complement relationships mean:

- and span all of : any uniquely decomposes as

- and span all of : any is perpendicular to

- Dimensions add up: and

Figure: Visual representation of the four fundamental subspaces and their relationships. [1]

Fundamental Theorems

Row Rank = Column Rank

The number of independent rows in a matrix is always equal to the number of independent columns. This number is the rank .

Why is this true? Consider a matrix:

Since :

- Basis of : , so

Looking at columns: and , while and are independent:

- Basis for : , so

The deep insight: Look at our basis rows and :

The "recipe" to build the dependent columns is written directly into the non-basis columns of the basis rows:

- To make : use . Those coefficients sit in column 2 of the basis rows.

- To make : use . Those coefficients sit in column 4 of the basis rows.

Similarly, looking at basis columns , the recipe to build is written in row 3 of the basis columns.

You can't add an independent row without also creating an independent column. The rank is the true number of "independent ingredients"—it dictates both how many independent rows and columns you can form.

Rank-Nullity Theorem

Example: Let transform .

Finding the rank: The output . Since , the third column is redundant.

- Basis for :

- rank — two input dimensions "survive"

Finding the nullity: Solve :

This gives and , with free. The nullspace is:

- Basis for :

- nullity — one input dimension "gets lost"

Verification: ✓

Every input dimension is accounted for: it either contributes to the output (pivot column) or gets nullified (free column).

Rank of Gram Matrix

For any matrix :

Similarly, .

Why this matters in ML: The matrix (the Gram matrix) appears in:

- Linear regression: Normal equations

- PCA: Covariance matrix is proportional to

- Optimization: Hessians of quadratic forms

If has linearly dependent columns (rank-deficient), then is also rank-deficient and singular (non-invertible). This causes:

- Cannot solve in normal equations

- "Singular matrix" errors in optimization

- Numerical instability

📌 Proof

Claim:

Forward direction (): If , then .

Backward direction (): If , multiply by :

Since , by Rank-Nullity:

Example: Let where .

- (only 2 independent columns)

- (also rank-deficient!)

This explains why perfect multicollinearity in regression makes the problem unsolvable: becomes singular.

Answering the Central Question: The solution set of is completely determined by the four fundamental subspaces of . When , solutions exist and form a coset : one particular solution plus any vector in the nullspace. The rank controls everything: it determines the dimensions of all four subspaces, dictates whether solutions exist (is in the column space?) and whether they are unique (is the nullspace trivial?).

Applications in Data Science and Machine Learning

The matrix shape determines which ML paradigm applies.

The Classical Regime: Skinny (m > n)

Scenario: 100 samples, 5 features → design matrix.

No hyperplane can pass through all data points perfectly. We project onto to find the "closest" fit.

The Deep Learning Regime: Fat (m < n)

Scenario: 10 samples, 1000 parameters → design matrix.

Infinite hyperplanes can pass through the data points. Among all zero-error solutions, we select the one with smallest norm.

Comparison Table

| Feature | Classical ML (Skinny ) | Deep Learning (Fat ) |

|---|---|---|

| System | Overdetermined (too many constraints) | Underdetermined (too much freedom) |

| Typical Rank | Full column rank () | Full row rank () |

| Nullspace | Trivial (unique coefficient mapping) | Nontrivial (collapses dimensions) |

| Solvability of | Usually impossible (target off the map) | Infinite solutions (affine plane) |

| Training Error | Non-zero (usually) | Exactly zero (perfect interpolation) |

| Goal | Minimize error: | Minimize norm: s.t. |

| Geometry | Projection (shadow of on ) | Selection (closest point to origin) |

The Valley Geometry (Fat Regime)

In the underdetermined case, the loss landscape has distinctive structure:

- The loss function is convex but not strictly convex

- Instead of a unique minimum (bowl shape), there's a flat region of zero-loss solutions (valley shape)

- Gradient descent rolls down and stops at the first zero-loss point it hits

- Key insight: Initialization at zero naturally finds the minimum norm solution because gradient descent stays in the row space throughout optimization

This valley geometry explains why:

- Deep networks can perfectly interpolate training data

- Regularization (Ridge) adds curvature to convert the valley into a bowl

- The implicit bias of gradient descent favors simpler (lower-norm) solutions

Guided Problems

These problems test your conceptual understanding of the Four Fundamental Subspaces, Rank, and Solvability. They minimize calculation and focus on the relationships defined by the Fundamental Theorem of Linear Algebra.

Problem 1: Rank-One Matrices and the Four Fundamental Subspaces

Let be a column vector in and be a column vector in . Neither vector is the zero vector.

We form the matrix by the outer product:

-

Find the rank of .

-

Find a basis and dimension for each of the four fundamental subspaces:

- Column Space

- Row Space

- Nullspace

- Left Nullspace

-

Describe the geometric condition for a vector to be in the nullspace.

💡 Solution

Hints:

- Rank: Write out the matrix multiplication . Notice that every column of is a scalar multiple of the vector . How many linearly independent columns does have?

- Column Space: Since every column is a multiple of , what single vector spans the entire column space?

- Row Space: Recall that . Alternatively, observe that every row is a multiple of .

- Nullspace: Use the Rank-Nullity Theorem: . To find the condition, write out and use associativity to group . For to be zero, what must be the value of the scalar ?

- Left Nullspace: Use the Fundamental Theorem: .

Solution:

-

Rank:

- Since and are non-zero, has at least one non-zero entry. All columns are multiples of , so there is only 1 independent column.

-

Four Fundamental Subspaces:

Column Space :

- Dimension:

- Basis:

Row Space :

- Dimension:

- Basis:

Nullspace :

- Dimension:

- Basis: Any linearly independent vectors orthogonal to

- The nullspace is an -dimensional hyperplane

Left Nullspace :

- Dimension:

- Basis: Any linearly independent vectors orthogonal to

- The left nullspace is an -dimensional hyperplane

-

Geometric Condition:

- A vector is in the nullspace if and only if is orthogonal to .

- Proof: . Since , we have if and only if .

- This means , which is a hyperplane perpendicular to .

Problem 2: Nullspace Preservation and the Gram Matrix

Let be a real matrix. We construct the square, symmetric matrix .

-

Nullspace Equality: Show that the nullspace of is exactly the same as the nullspace of . (i.e., prove )

-

Rank Relationship: Using the result from Part 1 and the Rank-Nullity Theorem, determine the relationship between and .

-

Invertibility Condition: Based on Part 2, if is a tall matrix () with linearly independent columns, is invertible? Explain your reasoning.

💡 Solution

Hints:

- Part 1: To show two sets are equal, prove both directions: (1) and (2) . For the second direction, if , multiply both sides by and use the fact that .

- Part 2: Use the Rank-Nullity Theorem: . Since and have the same nullspace dimension and the same number of columns, what can you conclude?

- Part 3: For invertibility, check if (full rank for a square matrix). What does "linearly independent columns" tell you about ?

Solution:

Part 1:

We need to show both directions:

(1) :

- Let , so .

- Then .

- Therefore .

(2) :

- Let , so .

- Multiply both sides by :

- Therefore , which means .

Since both inclusions hold, .

Part 2: Rank Relationship

From Part 1, we know , so:

Both and have columns. By the Rank-Nullity Theorem:

- For :

- For :

Since the nullspace dimensions are equal:

Part 3: Invertibility of

If is an tall matrix () with linearly independent columns:

- "Linearly independent columns" means (full column rank)

- From Part 2:

- is an square matrix with rank

Therefore, is invertible.

Key Insight: This is why the normal equations in linear regression have a unique solution when the columns of the design matrix are linearly independent (no perfect multicollinearity).

References

- MIT OpenCourseWare - 18.06SC Linear Algebra - The Four Fundamental Subspaces

- Strang, Gilbert - Introduction to Linear Algebra (Chapter 2)