Matrix Inverse and Invertibility

- The Central Question: Can We Undo a Transformation?

- Definition and Intuition

- Conditions for Invertibility

- Invertibility and the Four Fundamental Subspaces

- Computing the Inverse

- Properties of the Inverse

- The Determinant Test

- Applications in Data Science and Machine Learning

- Near-Singularity and Condition Number

- Guided Problems

- Summary

- References

The Central Question: Can We Undo a Transformation?

Consider a linear transformation that maps vectors from to . We encode this transformation as a matrix , and applying it to a vector gives us . The fundamental question of invertibility is this: given the output , can we uniquely recover the input ?

If the answer is "yes" for every possible , then the transformation preserves all information and can be undone. The matrix that undoes this transformation is called the inverse, denoted .

Definition and Intuition

A square matrix (of size ) is invertible (also called non-singular or non-degenerate) if there exists a matrix such that:

where is the identity matrix.

The inverse matrix , when it exists, is unique. Here's why: suppose both and are inverses of . Then:

Geometric Intuition: Think of as a machine that transforms vectors. The inverse is the machine that runs the transformation backwards. If stretches space by a factor of 2, then compresses it by a factor of 2. If rotates space by 30°, then rotates it by −30°.

Pseudo-inverse

Only square matrices can be invertible in the classical sense. A tall matrix () squeezes into a subspace of —you can't get back to the full . A wide matrix () collapses some directions—multiple inputs map to the same output, so you can't uniquely recover the input. For non-square matrices, we use the pseudo-inverse (Moore-Penrose inverse), which gives the "best" answer in a least-squares sense.

Example: Tall Matrix () — Not onto, can't reach all outputs

This matrix takes 2D vectors and embeds them into 3D:

The output is always in the -plane of . If someone gives you , there's no such that —you simply can't reach vectors with non-zero -component. No inverse can exist because the transformation isn't onto.

Example: Wide Matrix () — Not one-to-one, multiple inputs give same output

This matrix projects 3D vectors down to 2D. Consider these two different inputs:

Both inputs map to ! In fact, and differ by , which is in the nullspace. Given an output, you can't uniquely recover the input—the transformation isn't one-to-one. No inverse can exist.

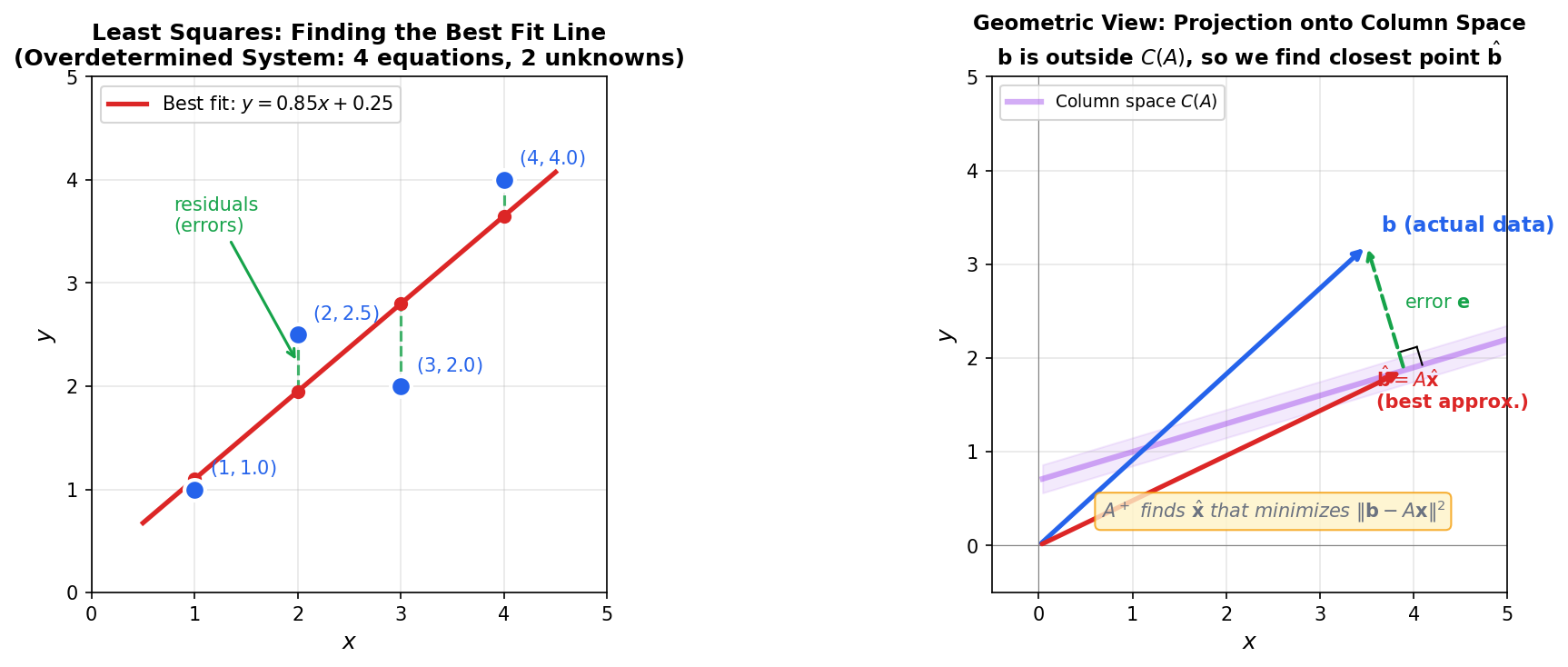

Example: Fitting a Line to Noisy Data

Suppose we have 4 data points and want to fit a line . This gives us 4 equations in 2 unknowns—an overdetermined system that generally has no exact solution. The pseudo-inverse finds the line that minimizes the sum of squared errors (residuals).

The left panel shows the data points (blue), the best-fit line (red), and the residuals (green dashed). The right panel shows the geometric interpretation: the target vector lies outside the column space of , so we project onto the closest point . The pseudo-inverse formula computes this projection directly.

Conditions for Invertibility

For a square matrix , the following conditions are all equivalent. If any one is true, they are all true. If any one is false, they are all false.

For an matrix , the following statements are equivalent:

- is invertible

- has full rank:

- The columns of are linearly independent

- The rows of are linearly independent

- The nullspace contains only the zero vector:

- The left nullspace contains only the zero vector:

- The column space is all of :

- The row space is all of :

- The equation has a unique solution for every

- The equation has only the trivial solution

- can be row-reduced to the identity matrix

- is a product of elementary matrices

- All eigenvalues of are non-zero

Why?

- Rank = n means all columns are independent (no redundancy), so they span all of

- If columns span , every is reachable, so always has a solution

- If columns are independent, has only , so , meaning solutions are unique

- If we can reach every with a unique , the transformation is one-to-one and onto—it's invertible

Invertibility and the Four Fundamental Subspaces

The four fundamental subspaces tell the complete story of when and why a matrix is invertible.

When is Invertible

For an invertible matrix :

| Subspace | Dimension | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Column Space | (reaches everywhere) | |

| Row Space | (uses all input directions) | |

| Nullspace | (no information lost) | |

| Left Nullspace | (no constraints on solvability) |

An invertible matrix "preserves information" completely. No dimensions are collapsed (nullspace is trivial), and every output is reachable (column space is full). The transformation is a perfect bijection between and .

When is Singular (Not Invertible)

When a square matrix is singular (not invertible), something has gone wrong:

| Subspace | What Happens | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Nullspace | Contains non-zero vectors | Multiple inputs give same output |

| Left Nullspace | Contains non-zero vectors | Some have no solution |

| Column Space | Smaller than | Can't reach all outputs |

| Row Space | Smaller than | Some input directions ignored |

Example: Consider the matrix

- Column 2 = 2 × Column 1, so the columns are dependent

- Nullspace: (a line)

- Column space: (a line, not all of )

This matrix collapses the line to zero. It's not one-to-one (multiple inputs give the same output), and it's not onto (can't reach most of ).

Non-Square Matrices: Structural Constraints

For an matrix (maps ), the shape alone determines certain limitations:

| Shape | Rank Bound | Column Space | Nullspace |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tall () | (never full) | Can be if full column rank | |

| Fat () | Can equal if full row rank | (always non-trivial) |

Tall matrices have more equations than unknowns. The column space lives in but has dimension at most , so it cannot fill . Most target vectors have no solution—the system is overdetermined.

Fat matrices have more unknowns than equations. The nullspace has dimension at least , so non-trivial vectors always get mapped to zero. Multiple inputs produce the same output—the system is underdetermined.

Only square matrices can potentially be both one-to-one (trivial nullspace) and onto (full column space) simultaneously.

Computing the Inverse

There are several methods to compute the inverse of a matrix. Each has its place depending on the context.

Method 1: Gauss-Jordan Elimination

The most general method works for any invertible matrix. The idea: apply the same row operations that reduce to to the identity matrix ; the result is .

Procedure: Form the augmented matrix and row-reduce to .

Example: Find the inverse of

Step 1: :

Step 2: :

Step 3: :

Step 4: :

Therefore:

Verification: ✓

Method 2: The 2×2 Formula

For matrices, there's a closed-form formula:

If and , then:

Method 3: The Adjugate Formula (General Case)

For any matrix:

where is the adjugate matrix (transpose of the matrix of cofactors). This formula is theoretically elegant but computationally expensive for large matrices.

Method 4: LU Decomposition

For numerical computation, factoring (lower × upper triangular) allows efficient solving of without explicitly computing . This is the standard approach in numerical libraries.

Properties of the Inverse

If and are invertible matrices, then:

- Inverse of inverse:

- Inverse of product: (note the reversed order!)

- Inverse of transpose:

- Inverse of scalar multiple: for

- Determinant of inverse:

Why does the product reverse? Think of putting on socks and shoes: if = "put on socks" and = "put on shoes", then must first undo (take off shoes), then undo (take off socks). Hence .

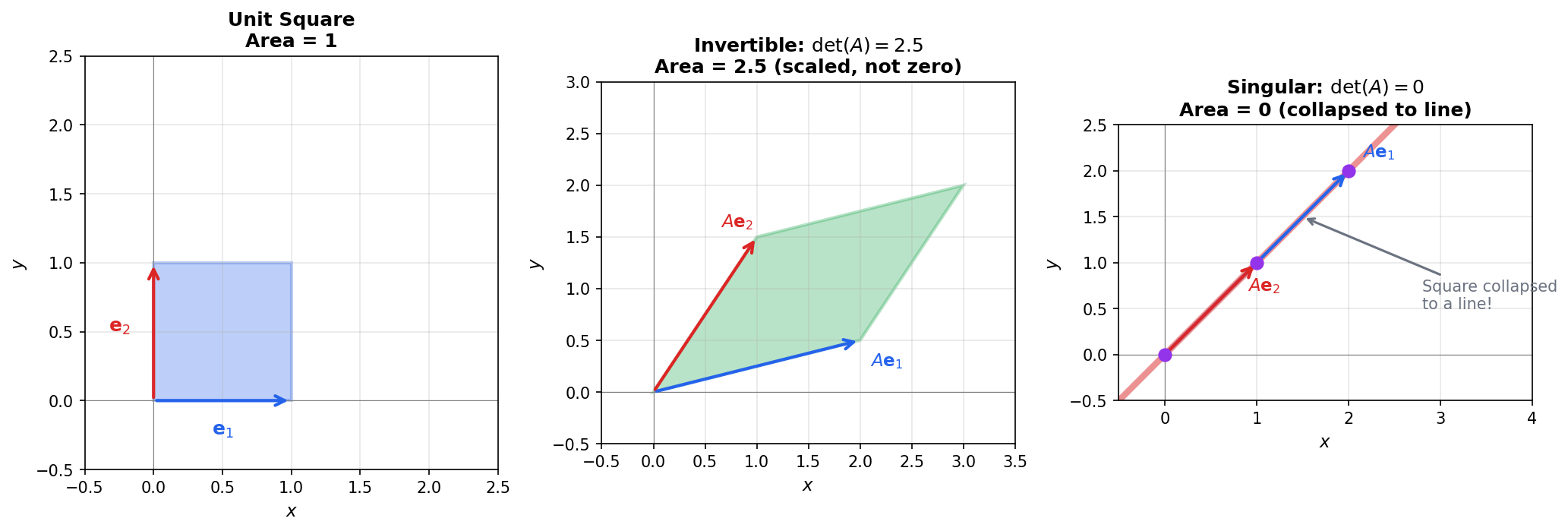

The Determinant Test

The determinant provides a single-number test for invertibility:

A square matrix is invertible if and only if .

The determinant measures the signed volume scaling factor of the transformation. If , the transformation collapses some dimension—the volume becomes zero. A collapsed dimension can't be recovered, so the matrix isn't invertible.

The unit square (left) transforms to a parallelogram with area . An invertible matrix (middle) scales area but keeps it non-zero. A singular matrix (right) collapses the square to a line—area becomes zero, and the original shape cannot be recovered.

Examples:

- → Invertible

- → Singular

Applications in Data Science and Machine Learning

1. Linear Regression (Ordinary Least Squares)

The normal equations for OLS are:

where is the design matrix ( samples, features), is the target vector, and are the coefficients we want to find.

The Gram Matrix must be invertible to get a unique solution:

When is invertible?

- The columns of must be linearly independent

- There must be no perfect multicollinearity (no feature is a linear combination of others)

- You need at least as many samples as features ()

What goes wrong when is singular?

When is singular, , meaning some non-zero vector satisfies .

Why ?

- : If , then .

- : If , multiply both sides by : . A vector with zero norm must be , so .

-

Non-unique coefficients: If is a solution, then is also a solution for any scalar , because . The solution space is an affine subspace, not a single point.

-

Interpretability breaks down: Suppose features (perfect multicollinearity). Then and produce identical predictions. You cannot attribute effect to individual features.

-

Numerical instability: Even if is technically invertible but nearly singular (high condition number), floating-point errors get amplified. A condition number of with double precision ( digits) leaves only reliable digits in .

2. Ridge Regression (Regularization)

When is singular or nearly singular, we add a regularization term:

Why does this help?

Adding eliminates the nullspace. Suppose , meaning . Then:

Taking the inner product with :

The left side is . The right side is when (and strictly negative if ). The only solution is . Therefore , so the matrix is invertible.

Eigenvalue perspective

The "flat direction" is an eigenvector of with a small eigenvalue . Eigenvalues measure curvature: means moving along changes the loss by only —nearly zero if .

If has eigenvalues , then has eigenvalues . The flat directions (small ) become steep (now ). If some (singular), adding shifts all eigenvalues positive, making the matrix invertible.

Trade-off: Regularization introduces bias (the solution is no longer exactly optimal for the training data) but reduces variance (the solution is more stable—small changes in data don't cause large swings in ).

When is nearly singular, there exists a direction where . The solution can "slide" along with almost no change in the loss . Small noise in can push far along this flat direction.

Adding penalizes movement in all directions equally. Now sliding along costs , anchoring the solution near the origin. The flatter the original direction, the more regularization helps.

3. Solving Linear Systems

Whenever we need to solve :

- Invertible : Unique solution

- Singular : Either no solution or infinitely many solutions

In practice, we rarely compute explicitly. Instead, we use matrix factorizations (LU, QR, Cholesky) that solve more efficiently and stably.

Near-Singularity and Condition Number

In numerical computing, a matrix can be "technically invertible" but still cause problems. This happens when the matrix is ill-conditioned—close to being singular.

The condition number of a matrix is:

or equivalently (for the 2-norm):

where and are the largest and smallest singular values of .

Interpretation:

- : Well-conditioned; small errors in cause small errors in

- : Ill-conditioned; small errors in can cause large errors in

- : Singular matrix

Example: Calculating

For (diagonal matrix):

- Singular values = absolute values of diagonal entries: ,

For (nearly singular):

- Compute

- Eigenvalues of : ,

- Singular values: ,

The tiny signals a nearly flat direction—small changes in along this direction get amplified by .

Rule of thumb: If and you're working with digits of precision, expect to lose about digits of accuracy when solving .

Practical advice:

- Check the condition number before inverting matrices

- Prefer factorization methods (LU, QR) over explicit inversion

- Use regularization for ill-conditioned problems

Guided Problems

Problem 1: When Does Adding a Row Make a Matrix Invertible?

Consider the matrix:

-

Is invertible? Explain why or why not using the shape of the matrix.

-

Suppose we add a third row to create a matrix . Can you choose a third row such that is invertible? If yes, give an example. If no, explain why.

-

Now consider removing a column from to get a matrix . Which column(s) can you remove to make invertible?

💡 Solution

Part 1: is not invertible because it's not square. A matrix maps . It has a non-trivial nullspace (dimension ), so multiple inputs map to the same output. No inverse can exist.

Part 2: We need to check if rows 1 and 2 are linearly independent first. Row 2 = Row 1 + , so they are independent.

For to be invertible, the third row must not be in the span of the first two rows.

Example: works.

Check: . ✓

Part 3: Removing column 3 gives , with . Invertible. ✓

Removing column 2 gives , with . Invertible. ✓

Removing column 1 gives , with . Invertible. ✓

All three choices work because no two columns of are parallel.

Problem 2: Symmetric Matrix and Diagonal Perturbation

Let be a symmetric matrix defined as follows:

-

Find the rank of and a basis for its Nullspace, . Is invertible?

-

Let be a positive scalar (e.g., ). We construct a new matrix by adding to the diagonal of :

Find the rank of this new matrix . Is invertible?

💡 Solution

Part 1: Analyzing Matrix

To find the rank and nullspace, we perform Gaussian elimination to reach Row Echelon Form.

Rearranging the zero row to the bottom:

- Rank: There are 3 pivots (in columns 1, 3, and 4). Therefore, .

- Invertibility: Since the rank (3) is less than the dimension (4), the matrix is singular (not invertible).

- Nullspace Basis: There is one free variable corresponding to column 2 (). The equation from row 1 is: . The other rows imply and . Setting free variable :

Part 2: Analyzing the Perturbed Matrix

We add (where ) to the diagonal elements of .

To check the rank/invertibility, we can check the determinant. Since the matrix is block diagonal, the determinant is the product of the determinants of the blocks.

Block 1 (Top-Left ):

Block 2 (Bottom-Right Diagonal): The determinants are simply the diagonal entries: and .

Total Determinant:

Conclusion: Since is positive (), every term in that product is positive. Therefore, .

- Invertibility: The matrix is invertible.

- Rank: Since it is invertible, it must have full rank. .

Connection Summary: Even though the original matrix lost information (rank 3, non-invertible), adding a small scalar matrix restored the rank to 4, making the system solvable for a unique solution. This is exactly what Ridge Regression does!

Problem 3: Linear Dependence and Gram Matrix

Let be a matrix defined as:

-

Determine if the columns of are linearly independent. If they are dependent, find a non-zero vector such that .

-

Calculate the symmetric matrix .

-

Without performing full Gaussian elimination on , determine the rank of and whether is invertible. Explain your reasoning based on the result from Part 1.

💡 Solution

Part 1: Linear Independence and Nullspace

We examine the columns of :

Since can be written as a linear combination of and , the columns are linearly dependent.

To find the vector (which is in the Nullspace ), we rewrite the dependency equation:

This gives us the coefficients for our vector :

Part 2: Calculating

Part 3: Rank and Invertibility of

Key Fact: (see Vector Spaces Deep Dive for proof)

- Rank of A: Since column 3 is dependent on columns 1 and 2 (and columns 1 and 2 are independent of each other), .

- Rank of G: Therefore, .

- Invertibility: The matrix is a matrix. For a matrix to be invertible, it must have full rank (rank = 3).

- Since , is not invertible (it is singular).

Mathematical Connection to Data Science

This problem illustrates Perfect Multicollinearity.

- The Matrix (Feature Matrix): Imagine represents your data. Column 1 is a bias term, Column 2 is "Feature A", and Column 3 is "Feature B". The math shows that Feature B is exactly Feature A plus the bias. They contain redundant information.

- The Vector (Non-uniqueness): The existence of a non-zero vector in the nullspace means there are infinite ways to combine the features to get the same result. The weights are not unique.

- The Matrix (Hessian/Gram Matrix): In optimization (OLS), we must invert . Because the columns were dependent, became singular. You literally cannot calculate , causing the algorithm to crash or output "NaN".

Problem 4: True or False — Invertibility Concepts

For each statement, determine if it is True or False. Justify your answer.

-

If and are both invertible matrices, then is also invertible.

-

If is invertible, then is invertible.

-

If , then .

-

If is invertible and , then .

💡 Solution

1. False.

Counterexample: Let and . Both are invertible, but , which is not invertible.

2. True.

If is invertible, then . Since , we have , which means . Therefore is invertible.

3. True (when and are square matrices of the same size).

If , then is a right inverse of . For square matrices, a right inverse is also a left inverse.

Proof: From , we have , so and . Thus both and are invertible. Then . So .

4. True.

If , then . Since is invertible, , so , meaning .

Alternatively: multiply both sides by : , giving .

Summary

Invertibility fundamentals:

- A square matrix is invertible if ; the inverse is unique when it exists

- Non-square matrices cannot be invertible: tall matrices aren't onto, wide matrices aren't one-to-one

- For non-square systems, the pseudo-inverse provides the least-squares best answer

Equivalent conditions (Invertible Matrix Theorem):

- Full rank ()

- Linearly independent columns (and rows)

- Trivial nullspace:

- Non-zero determinant:

- Column space spans :

Four fundamental subspaces view:

- Invertible: all four subspaces have "perfect" dimensions (column/row space = , nullspaces = )

- Singular: some dimension collapses (non-trivial nullspace), some outputs unreachable (column space )

Computing and testing:

- Gauss-Jordan elimination: row-reduce to

- The formula:

- Determinant test: iff the transformation collapses volume to zero

Applications:

- Linear regression requires ; singular means non-unique coefficients

- Ridge regression adds to eliminate the nullspace, guaranteeing invertibility

- Condition number measures numerical stability; high amplifies errors

References

- Strang, Gilbert - Introduction to Linear Algebra (Chapters 2-3)

- MIT OpenCourseWare - 18.06SC Linear Algebra

- Golub, Gene H. and Van Loan, Charles F. - Matrix Computations (Chapter 2)